Minnesota Metropolitan Regional Trauma Advisory Committee Geriatric Resource

PURPOSE

Provide a resource with a variety of geriatric care options for any level of Trauma Center. This resource includes multiple strategies on how to manage/care for geriatric trauma patients. Per the American College of Surgeons 2022 Standards, Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient, Level I and II trauma centers must have care protocols for injured older adult.

Disclaimer: This resource is for general use with most patients; providers should use their independent clinical judgement. This resource is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

CONTENTS

-

- Tools:

-

- Identification of Seniors At-Risk Tool (ISAR)

- 6 question survey

- >1 positive response is considered high-risk

- >= 2 has been associated with a greater likelihood of functional decline, nursing home admission, long-term hospitalization, or death.

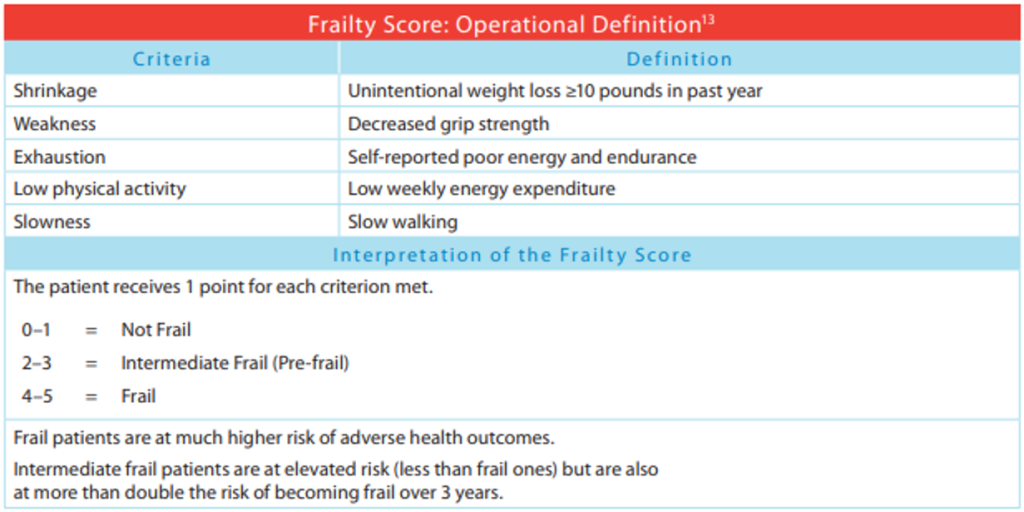

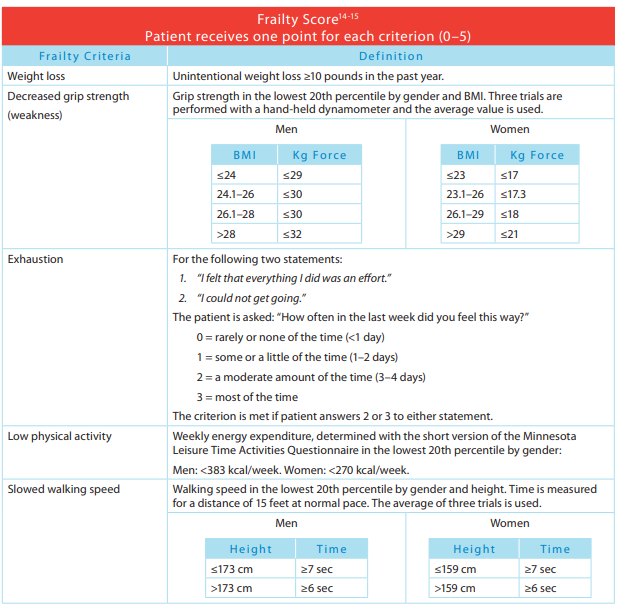

- Frailty Score

- 5 criteria are evaluated

- Patient receives 1 point for each criterion met

- 0-1 = Not frail

- 2-3 = Intermediate frail (Pre-frail)

- 4-5 = Frail

- FRAIL

- 5 questions

- Scoring: ≥3/5 criteria met indicates frailty

- 5 questions

- Patient receives 1 point for each criterion met

- 5 criteria are evaluated

- 6 question survey

- Identification of Seniors At-Risk Tool (ISAR)

1-2/5 indicates pre-or-intermediate frailty

0/5 indicates non-frail.

- PRISMA Frailty Assessment

- 7 questions

- 3 or more “yes” answers indicate an increased risk for frailty and need for clinical review.

- 7 questions

- Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS)

- 9 nine-point scale

- Number of questions depends on the degree of frailty

- 0 – 3 very fit to managing well

- 4 – 6 vulnerable to moderately frail

- 7 – 9 severe frailty to terminally ill

- Number of questions depends on the degree of frailty

- 9 nine-point scale

Things to consider with implementation:

- All patients noted to be at high-risk requiring admission to the hospital should be referred to case management upon admission with the risk assessment results communicated.

- Concerns for elder abuse should be reported to MDH as a vulnerable adult

-

Consider the following list to identify these patients who should get a specialty consult:

· Screening results that indicate frailty in 65 years and older

· Anyone > to 85 years of age

· Impaired cognition

· Delirium risk

· Impaired functional status

· Impaired mobility

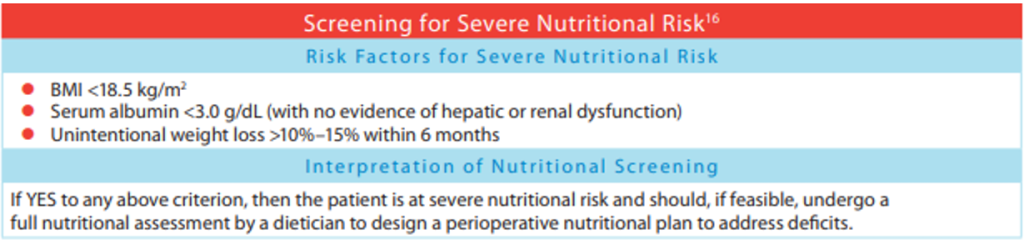

· Malnutrition

· Difficulty swallowing

· Need for Palliative Care assessment

-

DEMENTIA:

- Prevention: There are 12 potentially modifiable risk factors that have been found to be associated with dementia. These include hypertension, diabetes, obesity and lack of physical activity, smoking, high alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet, depression, traumatic brain injury, social isolation, air pollution, and hearing loss. Research has found that lifestyle modification aimed at specific risk factors could decrease the incidence of dementia by 40%.

- Identification: There is insufficient evidence to support dementia screening among people who do not exhibit signs of dementia. But early identification is important and when changes in cognition, behavior, mood, and/or function are observed or reported, screening should occur. Earlier detection allows for improved brain health, better management symptoms, and early capture of their care preferences. Diagnosis can be made with cognitive/neurological tests, brain scans, psychiatric evaluation, genetic testing, and CSF and blood tests.

- When signs/symptoms of dementia are observed or reported, screen patients age 65 and over. It is recommended to establish clinical workflow integration for documentation within your EMR. There are various screening tool options available:

- Short BleSSed Test (SBT)

- Weighted six-item instrument designed to identify dementia.

- Evaluates orientation, registration, and attention.

- Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS)

- Can be used to rapidly assess elderly patients for the possibility of dementia

- Consists of 10 questions, each worth one point.

- Score of 6 or less is suggestive of delirium or dementia. Further testing is necessary to confirm a diagnosis.

- Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS)

- 6-item scale that assesses the cognitive domains of memory, praxis, language, judgement, drawing, and body orientation.

- MiniCog

- Considered a routine ‘cognitive vital sign’ measure.

- A composite of three-item recall and clock-drawing

- Short BleSSed Test (SBT)

- When signs/symptoms of dementia are observed or reported, screen patients age 65 and over. It is recommended to establish clinical workflow integration for documentation within your EMR. There are various screening tool options available:

- Management: The overall goal for managing dementia is to reduce suffering caused by the cognitive and accompanying symptoms while delaying progressive cognitive decline. This is most often done by using both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches. Ideas for these approaches are found below in the Interventions

- Interventions

- Implement a geriatric specific order-set to highlight care considerations for patients with dementia. Consider including items like: a pain assessment scoring tool for dementia patients, non-pharmacological treatments including music therapy, massage, sensory stimulation, and aromatherapy. Also include development of personal care routines and assurance of effective communication practices.

- If patients have not yet been started on medications aimed at symptomatic benefits for cognitive symptoms, ensure that they receive prompt follow-up after hospital discharge to be evaluated by their PCP.

- Provide a 4M’s Educational Brochure to patients age 65 and over. 4M’s Provider Toolkit and 4M’s Patient Brochure

- The four M’s include: what Matters, Mobility, Medication, and M The intent is to provide a guide for older adults and their families to evaluate how they think about the 4M’s and develop resources to help them proactively interact with their health care team.

- Other Considerations

- Recommend follow-up with a PCP for further evaluation if concerns are noted.

- Screening is only one small part of a comprehensive assessment and is not a conclusive diagnosis

- If a person is acutely ill or is experiencing delirium, it is recommended that health-care providers postpone in-depth dementia assessments and a diagnosis until the person is stable and reversible causes are addressed.

- Clinical guidelines suggest that depression be treated before a dementia diagnosis is made

- Assessment for dementia should be conducted after delirium screening.

DEPRESSION:

- Prevention: The ability to prevent depression is unknown. However, it is necessary for health care providers to place their focus on identification.

- Identification: Health-care providers must be vigilant for depression among older adults, and assess for depression whenever risk factors or signs and symptoms are present. Unfortunately, depression is often not recognized, is under-diagnosed, and frequently goes untreated. Furthermore, few older adults actively seek treatment or see a mental health specialist to manage their depression. A detailed assessment for depression should occur when risk factors are present or when depression is suspected

- When signs/symptoms of depression are observed or reported, screening should be completed. It is recommended to establish clinical workflow integration for documentation within your EMR. There are various screening tool options available:

- Geriatric Depression Scale

- Provides a quantitative rating of depression

- Available in 15-questions or 30-question All questions are YES/NO

- Patient Health Questionaire-2 (PHQ-2)

- “First Step” approach with two-question screening regarding the frequency of depressed mood and anhedonia over the past two weeks

- If the patient has a positive screen (3 or above), proceed to further screening with the PHQ-9.

- Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

- Used for diagnosing, monitoring, and measuring the severity of depression

- Nine question screening regarding the frequency of depressed mood and anhedonia over the past two weeks

- Management: Health-care providers should ensure that follow-up support and resources are available for older adults who are identified as having depression. Experts suggests that qualified health-care professionals may include a primary care practitioner, psychiatrist, or a psychogeriatric/geriatric mental health specialist. Other referrals to members of the health-care team may be necessary, especially to rule out or assess for co-morbid conditions that may mimic depression. If there is active suicidal ideation/risk of a person killing himself/herself, or if a person with depression presents a considerable immediate threat or harm to others, it is important to seek urgent attention from a qualified professional. A variety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies with varying degrees of efficacy are available in clinical guidelines. When selecting treatment, health-care providers should start with the least invasive and most effective

- Interventions

- Implement a Geriatric specific order-set to include screenings and referrals for those identified as high likelihood or at risk for depression.

- Other Considerations:

- Due to the high prevalence of depression in people with dementia, health-care providers may need to consider the impact that co-morbid dementia has on individuals with depression. When these conditions co-exist, healthcare providers can offer many of the same interventions as they would for a person who only has depression, making any necessary adjustments to the approach and duration of the interventions.

DELIRIUM:

Delirium is defined as an abrupt change in the brain that causes mental confusion, emotional disruption, and/or perceptual disturbances. Delirium increases a patient’s risk of morbidity and mortality, contributes to longer length of stays, and increases health care costs. It develops over a short period (hours to days) and fluctuates over time. Delirium is classified as: hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed. Hypoactive delirium is often mistaken for depression or dementia. Delirium is often underrecognized.

- Prevention (prevention and management interventions often overlap)

- Pre-Op optimization (pain control, med management, education)

- Post-Op mobility and pain management

- Lighting: Soft light is recommended, but exposure to nature light is also shown to be beneficial for recovery times and decreasing delirium.

- Acoustic Orientation Improvements: private rooms or acoustically enhanced drapes, if necessary, for better communication and decrease levels of anxiety and delirium.

- Sleep hygiene – promote quiet and uninterrupted sleep

- Provide sensory aids (hearing aids, dentures, glasses)

- Provide frequent re-orientation

- Limit physical restraints

- Provide patient and family education brochure on delirium

- Identification

- Implement routine screenings for injured patients age 65 and over. It is recommended to establish clinical workflow integration for documentation within your EMR.

- 4AT

- Include four items: Alertness – Abbreviated Mental Test-4 – Attention – Acute Change or Fluctuating Course

- Scored from 0 to 12. Each of the four categories are assessed and scored. The sum of the 4 scores is the total.

- Can be used on patient too drowsy to engage in testing or conversation since a score is provided instead of N/A or not-testable.

- Confusion Assessment Measuring Instrument (CAM)

- This is considered the “gold standard” for screening for delirium

- Has sensitivity of 94-100%, specificity of 90-95% and high interobserver reliability

- Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu DESC)

- Continuous, observational five-item scale

- Recognizing Active Delirium As part of your Routine (RADAR) 18-19

- Three-step process to identify delirium in the elderly population

- Observation of three signs of altered LOC and inattention with each medication delivery.

- There are also outpatient/Emergency Department screening options available:

- 4AT

- Implement routine screenings for injured patients age 65 and over. It is recommended to establish clinical workflow integration for documentation within your EMR.

- Management

- It is important to treat delirium when it occurs. Prioritization must be given to the following items:

- Pain assessment and management

- Consider restlessness as an indicator of pain

- Schedule acetaminophen

- Utilize Ice/heat modalities

- Activity and mobility

- Providers need to place expectation of mobility on patient/staff/family

- Up to chair for all meals

- Walking 2-3 times per day

- Update activity orders as needed – d/c bedrest orders

- Sleep interventions and promotion

- Shades open/lights on during day 8a-8p

- Daytime activity/mobility to promote fatigue for sleep at night

- Minimize nighttime interruptions (cluster cares)

- Patient/Family education

- Reduce lines/tethers

- Sensory interventions

- Cognitive stimulation/orientation

- Providers need to place expectation of mobility on patient/staff/family

- Upon diagnosis of acute delirium, attention should be paid to underlying causes including, but not limited to:

- Infections: Commonly due to UTI or pneumonia

- Medications: Including: Anti-cholinergic medications, sedative/hypnotics, narcotics, and any new medication, especially if multiple medications have been recently added

- Electrolyte imbalances

- Alcohol/drug use or withdrawal

- Interventions

- Implement a Geriatric specific order-set to include screenings and prevention measures, and precautions.

- Pain assessment and management

- It is important to treat delirium when it occurs. Prioritization must be given to the following items:

- Other considerations

- New focal neurologic findings should guide an evaluation for stroke syndromes

- Coordination of care, with special attention to directing interventions towards improving reversible causes and limiting factors that extend or cause delirium is the main goal.

As mental status changes wax and wane, delirium screening should be reevaluated on a regular basis.

-

· Things to consider

o Discuss with family, surrogates, and health care team and document in medical record the following items:

§ Patient’s priorities and preferences regarding treatment options (including operative and nonoperative alternatives)

§ Postinjury risks of complications, mortality and temporary/permanent functional decline

§ Advance directives or living will and how these will affect initial care and life sustaining preferences

§ Identify surrogate decision maker, medical proxy or legal guardian

§ Make liberal use of palliative care options

§ In appropriate settings, hospice bay be a positive, active treatment option

o Hold family meeting within 72 hours of admission to discuss goals of care

· Tools

o polst.org/form-patients POLST is portable medical orders of important treatment decisions. It is designed for patients with advanced disease, frailty, or terminal conditions.

o www.lightthelegacy.org Formerly Honoring Choices. Resource to find more information about healthcare directives. Forms are available in multiple languages

-

Document the patient’s complete medication list, including over the counter and complementary/ alternative medications.

- Tools

- BEERS Criteria – identifies potentially inappropriate medication use in adults over age 65

- Pharmacy medication reconciliation

- Ideas of where to find current med list

- Surescript- used for exchange of health information between health care organizations and pharmacies

- Care everywhere

- Clinic notes- anticoagulation clinic, psychiatric

- Skilled nursing facility/group home medication administration record

- Medication list will be screened by both the nurse and provider for:

- Polypharmacy >5 medications

- Presence of high-risk medications

- See “Beers criteria” as example of high risk medications

- MTMS – Medication Therapy Management Services (state.mn.us) – pharmacists work with patients and providers to solve problems related to medications in the outpatient setting.

- Ideas of where to find current med list

Services include the following:

- Performing or obtaining necessary assessments of the member’s health status

- Face-to-face or telehealth encounters done in any of the following:

- Ambulatory care outpatient setting

- Clinics

- Pharmacies

- Member’s home or place of residence if the member does not reside in a skilled nursing facility

- Formulating a medication treatment plan

- Monitoring and evaluating the member’s response to therapy, including safety and effectiveness

- Performing a comprehensive medication review to identify, resolve and prevent medication-related problems, including adverse drug events

- Documenting the care delivered and communicating essential information to the member’s other primary care providers

- Providing verbal education and training designed to enhance member understanding and appropriate use of the member’s medications

- Providing information, support services and resources designed to enhance patient adherence with the patient’s therapeutic regimens

- Coordinating and integrating medication therapy management services within the broader health care management services being provided to the member

Eligible Members: Medical Assistance (MA) and MinnesotaCare (fee-for-service and managed care) members are eligible for MTMS if they are all of the following:

- An outpatient (not inpatient or in an institutional setting)

- Not eligible for Medicare Part D

- Taking a prescription medication to treat or prevent one or more chronic conditions

- Pain Management Strategies

- Use elderly-appropriate medications and dosing.

- Avoid Benzodiazepines.

- Consider early use of non-narcotics including scheduled Tylenol, NSAIDs, adjuncts and IV Ketamine.

- Monitor use of narcotics; consider early implementation of patient-controlled analgesia.

- Epidural or regional algesia may be preferable to other means for patients with multiple rib fractures to avoid respiratory failure.

- Things to consider

- Geriatric patients are at high-risk for adverse events related to medications. The aging population tends to take more medications, have more co-morbidities, and have differing response to medications when compared to their younger cohorts.

- The normal aging physiology often leads to change in metabolism with medications as well as problematic response to “normal” medication dosing.

- Medication list should be be obtained and completed as accurately as possible, taking advantage of patients, caretakers, and medical record resources.

- Patients taking more than 5 medications, any high-risk medications, or presenting with signs or symptoms of adverse drug events should be be managed with a multi-disciplinary approach focused on improving patient outcomes.

- Establish medication “reconciliation” tool

- High risk medication list may be hospital specific and should minimally include:

- Anticoagulants and antiplatelets

- Anti-hyperglycemics

- Cardiac medications including digoxin, amiodarone, B-blockers, Ca channel blockers

- Diuretics

- Narcotics

- Anti-psychotics and other psychiatric medications

- Immunosuppressant medications, including chemotherapy agents

- Multi-disciplinary team including pharmacy should work with provider to minimize drug-drug interactions, minimizing polypharmacy and high-risk medications

- Discontinue non-essential medications

- Continue medications with withdrawal potential

- Speech and swallow eval to assure ability to swallow pills

- Palliative care or pain service consult

- Imbed decision support tools and alerts within the electronic health record for potentially inappropriate medication is prescribed

- Tools

-

Trauma is one of the leading causes of death in the geriatric population. Falls, even relatively minor impact falls, often represent a major traumatic mechanism in the geriatric population and can lead to significant morbidity and mortality compared to younger patients.

- Tools

- Assessing baseline current functional status in ambulatory patients

- Short simple screening test for functional assessment – TQIP Geriatric Guideline appendix

- 4 question survey

- If no to any of the questions, then a more in-depth evaluation should be performed including full screening of ADLs and IADLs.

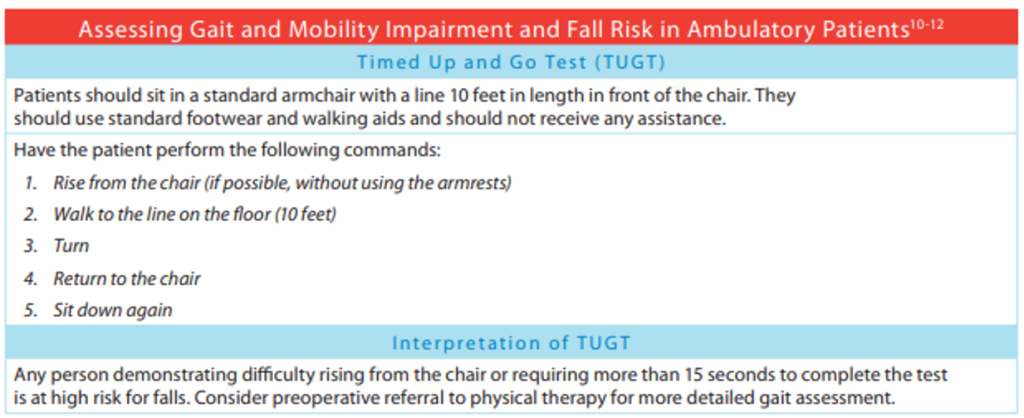

- Assessing gait and mobility impairment and fall risk in ambulatory patients

- Timed up and Go Test (TUGT) – TQIP Geriatric Guideline appendix TUG_(cdc.gov)

- Patient asked to perform 5 tasks

- Any difficulty getting up from chair or takes more than 15 seconds to complete task then pt is at high risk for fall.

- Adult Bedside Mobility Assessment Tool (BMAT) for Nurses BMAT (myamericannurse.com)

- Assesses ability to sit, stretch, stand, and walk.

- Includes a safety screen assessment.

- Simple instructions for the screening clinician, with a pass/fail determination which stops the assessment or moves through the 4 areas.

- 4-Stage Balance Test (cdc.gov)

- Simple test

- Assess balance while standing in 4 different positions for 10 seconds.

- Initiate a comprehensive evaluation for geriatric patients presenting after a fall or for those who may be at high risk for future falls.

- An appropriate tool is a direct, easily implemented tool to screen for risk of falls

- In traumatically injured patients, functional ability, including gait and fall risk, should be assessed as early as possible and compared with established baseline function.

- Timed up and Go Test (TUGT) – TQIP Geriatric Guideline appendix TUG_(cdc.gov)

- Short simple screening test for functional assessment – TQIP Geriatric Guideline appendix

- Assessing baseline current functional status in ambulatory patients

- Things to Consider

- The appropriate evaluation of a patient who either has fallen or is high risk of falling involves not only a thorough assessment for traumatic injuries, but an assessment of the cause of the fall and estimation of future fall risk.

- The goal of the evaluation of a patient who has fallen or is at increased risk of falling is to diagnose and treat traumatic injuries, discover, and manage the predisposing causes of the fall, and ultimately to prevent complications of falling and future falls.

- If the patient was a healthy 20-year-old, would he/she have fallen? If answer is “no,” then an assessment of the underlying cause of the fall should be more comprehensive and should include:

- History is the most critical component of the evaluation of a patient with, or at risk for, a fall. Several studies and authorities have suggested that there are several key elements to an appropriate history in patients that fall. Key historical elements include:

- Age greater than 65

- Location and cause of fall

- Difficulty with gait and/or balance

- Number of previous falls

- Time spent on floor or ground

- LOS/AMS

- Near/syncope/orthostasis

- Melena

- Specific comorbidities such as dementia, Parkinson’s, stroke, DM, hip fracture and depression

- Visual or neurological impairments such as peripheral neuropathies

- Alcohol use

- Medications

- ADL’s

- Appropriate footwear

- Although there is no recommended set of diagnostic tests for the cause of a fall, a low threshold should be maintained for obtaining an EKG, complete blood count, standard electrolyte panel, measurable medication levels and appropriate imaging.

- Develop a plan for early mobilization. Ensure ambulation within 48 hours of admission.

- History is the most critical component of the evaluation of a patient with, or at risk for, a fall. Several studies and authorities have suggested that there are several key elements to an appropriate history in patients that fall. Key historical elements include:

- Tools

-

- Tools

- Emergency Department

- Evaluate patient’s gait

- Get up and go test

- In-patient

- Physical and Occupational Therapy Consult

- IDEAL Discharge Planning Overview, Process, and Checklist

- Includes five key elements for assessment.

- Checklists integrate safe discharge planning process beginning the day of admission.

- IDEAL Discharge Planning Tool

- Emergency Department

- Things to Consider

- Patients not able to rise from the bed, turn, and steadily ambulate out of the ED should be reassessed. Admission should be considered if patient safety cannot be assured.

- Begin developing plan for transition to posthospital care or special unit care in the immediate postinjury period.

- Assess following discharge planning issues early during hospitalization

- Home environment, social support, and possible needs for medical equipment and/or home health services.

- Patient acceptance/denial of nursing home or skilled nursing facility placement

- Provide the patient and caregiver with a written discharge document which includes:

- Discharge diagnosis

- Medications and clear dosing instructions and possible reactions

- Documentation of reconciliation between outpatient and inpatient medications

- Direction for wound care

- Instructions for diet (nutrition plan) and mobility

- Needs for PT/OT

- Contact information for patients physician or clinic

- Establish an appointment with continuity physician, specialty physicians, or clinic

- Clear documentation of incidental findings

- Documentation of follow up appointment with telephone contact

- Communicate results of hospitalization with patient’s primary care provider (PCP)

- Provide PCP with discharge summary

- Provide the receiving facility with a discharge summary prior the patients departure from the hospital as well as verbal communication with the receiving facility.

- For patients discharged to home:

- Arrange for home health visit or follow-up phone call within 1-3 days of discharge to assess.

- Pain control

- Tolerance of food, liquids

- Ability to ambulate

- Mental status

- Understanding of post discharge instructions/medications

- Arrange for home health visit or follow-up phone call within 1-3 days of discharge to assess.

- Tools

-

FALL PREVENTION FOR AGING ADULTS

Falls are the second leading cause of unintentional injury deaths worldwide.[1] In the United States in 2021, falls were the leading cause of non-fatal emergency room visits for all ages and the leading cause of death for people 65 years or older.[2] However, falling in later adulthood should not be considered a normal part of aging.[3] Yet, emergency room visit rates for falls continue to increase over time and each year an estimated $50 billion is spent on non-fatal fall injuries with an estimated $754 million spent on fatal falls.[4] [5] [6]

Falls in older adults are caused by multiple factors such as lower body weakness, vitamin D deficiency, difficulty with walking and balance, use of various medications, foot pain or footwear and home hazards; therefore, a multidisciplinary approach to prevention is needed.[7] [8] [9] Furthermore, a systematic approach to identifying fall risk and offering intervention strategies whether single or multifactorial has been described as feasible and may have the most impact on preventing falls in community dwelling older adults.[10] [11] [12] [13]

Falls may result in a loss of independence, chronic pain, and reduced quality of life, and it is far more effective to focus on prevention rather than management of the injuries afterwards9. A study by Boyd & Stevens[14]showed a significant association between recent falls and a fear of falling. A fear of falling has been shown to have negative health outcomes such as a decreased quality of life, functional limitations, restricted activity, and depression.14 [15] Yet many older adults do not admit to or recognize their risk of falling and have a low perceived risk of falling.[16] [17] However, the statistics represent an altogether different reality with falls being a leading cause of unintentional injury and fatality in those aged 65 and older.[18] [19]

STEADI

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed a fall prevention initiative called Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) to assist healthcare providers in preventing falls by screening patients for fall risk and assessing modifiable risk factors in order to provide interventions aimed at reducing fall risk.[20] [21] As part of this CDC program (2023), clinical resources are offered to healthcare professionals including an algorithm for screening, assessment and intervention of the at-risk fall patient.

The STEADI Clinical Resources toolkit is a broad, evidence-based resource intended for healthcare providers to assess fall risk and develop individualized interventions.[22] Assessments include, but are not limited to, evaluation of gait, home hazard assessment, medication review, vision assessment, vitamin D intake, and assessment of common comorbidities such as depression and anxiety.

EXERCISE

Of the multiple factors contributing to fall risk, exercise programs for community-dwelling older adults have been shown to reduce fall risk, with balance and strength exercises having a positive relationship with one another.[23] [24] [25] [26] [27]

Exercise and health programming information is available from the National Institute on Aging. This is a program of the National Institute of Health (NIH) and includes tips on how to stay motivated, exercise with chronic conditions and provides a thorough overview of the Four Types of Exercise that can improve health and physical ability. The four types of exercise outlined by the NIA include endurance, strength, balance, and flexibility.

AREA AGENCY ON AGING

In Minnesota, Trellis is the designated Area Agency on Aging for the Twin Cities metro area, serving individuals and organizations in Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, and Washington counties. However, many of Trellis’ initiatives and activities have a broader geographic reach across the state (https://trellisconnects.org/about/). One such program of Trellis, Juniper, is a resource for community-based fall prevention programs such as A Matter of Balance, Stay Active and Independent for Life, Stepping On, and Tai Ji Quan: Moving for Better Balance. In addition to fall prevention classes, Juniper offers other Get Fit and Live Well classes for the aging adult.

When planning fall prevention programs or activities, it is important to consider the multiple factors that contribute to an aging adult’s fall risk. You will find additional tools and links under the RESOURCES tab.

[1] World Health Organization (updated Apr 26, 2021). Falls. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheet/detail.falls

[2] Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (updated Oct 28, 2024). Older Adult Falls Data. https://www.cdc.gov/falls/data-research/index.html

[3] National Council on Aging (2023). Get the facts on falls prevention. https://ncoa.org/article/get-the-facts-on-falls-prevention

[4] National Institute on Aging (n.d.). Falls and fractures in older adults: causes and prevention. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/falls-and-fractures-older-adults-causes-and-prevention

[5] Shankar, K.N., Liu, S.W. & Ganz, D.A. (2017). Trends and characteristics of emergency department visits for fall-related injuries in older adults, 2003-2010. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(5), 785-793.

[6] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (n.d.). Cost of older adult falls. https://www.cdc.gov/falls/data/fall-cost.html

[7] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (April 27, 2023). About STEADI. https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/about.htm

[8] Pereira, C.B. & Kanashiro, A.M.K. (2022). Falls in older adults: a practical approach. Balance Disorders and Neuro-Otology, 80(5 Suppl. 1), 313-323. doi:10.1590/0004-282X-ANP-20220S107

[9] Vaishya, R. & Vaish, A. (2020). Falls in Older Adults are Serious. Indian Journal of Orthopedics., 54(1):69-74. doi: 10.1007/s43465-019-00037-x. PMID: 32257019; PMCID: PMC7093636.

[10] Bolding, D.J. & Corman, E. (2019). Falls in the geriatric patient. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 35, 115-126. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2018.08.010.

[11] Dautzenberg, L., Beglinger, S., Tsokani, S., Zevgiti, S., Raijmann, R.C.M.A., Rodondi, N., Scholten, R.J.P.M., Rutjes, A.W.S., Di Nisio, M., Emmelot-Vonk, M., Tricco, A.C., Straus, S.E., Thomas, S., Bretagne, L., Knol, W., Mavridis, D. & Koek, H.L. (2021). Interventions for preventing falls and fall-related fractures in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69, 2973-2984.

[12] Pereira, C.B. & Kanashiro, A.M.K. (2022). Falls in older adults: a practical approach. Balance Disorders and Neuro-Otology, 80(5 Suppl. 1), 313-323. doi:10.1590/0004-282X-ANP-20220S107

[13] Pfortmueller, C.A., Lindner, G. & Exadaktylos, A.K. (2014). Reducing fall risk in the elderly: risk factors and fall prevention, a systematic review. Minerva Medica, 105(4), 275-281.

[14] Boyd, R. & Stevens, J.A. (2009). Falls and fear of falling: burden, beliefs and behaviours. Age and Ageing, 38, 423-428.

[15] Liu, M., Hou, T., Li, Y., Sun, X., Szanton, S.L., Clemson, L. & Davidson, P.M. (2021). Fear of falling is as important as multiple previous falls in terms of limiting daily activities: a longitudinal study. BMC Geriatrics, 21, 350. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02305-8

[16] Hughes, K., van Beurden, E., Eakin, E.G., Barnett, L.M., Patterson, E., Backhouse, J., Jones, S., Hauser, D., Beard, J.R. & Newman, B. (2008). Older persons’ perception of risk of falling: Implications for fall-prevention campaigns. American Journal of Public Health, 98(2), 351-357.

[17] Stevens, J.A., Sleet, D.A. & Rubenstein, L.Z. (2017). The influence of older adults’ beliefs and attitudes on adopting fall prevention behaviors. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 12(4), 324-330.

[18] Rosen, T., Mack, K.A. & Noonan, R.K. (2013). Slipping and tripping: fall injuries in adults associated with rugs and carpets. Journal of Injury & Violence Research, 5(1), 1-69.

[19] WISQARS (2021). Explore leading causes of death. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/lcd/?o=LCD&y1=2021&y2=2021&ct=10&cc=ALL&g=00&s=0&r=0&ry=0&e=0&ar=lcd1age&at=groups&ag=lcd1age&a1=0&a2=199

[20] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (April 27, 2023). About STEADI. https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/about.htm

[21] Lee, R. (2017). The CDC’s STEADI initiative: promoting older adult health and independence through fall prevention. American Family Physician, 96(4), 220-221.

[22] Stevens, J.A. (2013). The STEADI toolkit: a fall prevention resource for healthcare providers. Indian Health Services Primary Care Provider, 39(9), 162-166.

[23] Rikkonen, T., Sund, R., Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Sirola, J., Honkanen,R. & Kroger, H. (2023). Effectiveness of exercise on fall prevention in community-dwelling older adults: a 2-year randomized controlled study of 914 women. Age and Ageing, 52, 1-9.

[24] Sadaqa, M., Nemeth, Z., Makai, A., Premusz, V. & Hock, M. (2023). Effectiveness of exercise interventions on fall prevention in ambulatory community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. Frontiers in Public Health. Doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1209319.

[25] Sherrington, C., Michaleff, Z.A., Fairhall, N., Paul, S.S., Tiedemann, A., Whitney, J., Cumming, R.G., Herbert, R.D., Close, J.C.T. & Lord, S.R. (2017). Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51, 1749-1757.

[26] Sun, M., Min, L., Xu, N., Huang, L. & Li, X. (2021). The effect of exercise intervention on reducing fall risk in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 12562.

[27] Thomas, E., Battaglia, G., Patti, A., Brusa, J., Leonardi, V., Palma, A. &Bellafiore, M. (2019). Physical activity programs for balance and fall prevention in elderly. A systematic review. Medicine, 98(27), e16218.

RESOURCES

-

- Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program (GEDA) Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation (acep.org)

- TQIP – Geriatric Best Practice Guideline geriatric guidelines.pdf (facs.org)

- American Geriatrics Society BEERS Criteria 2023

- Optimal Resources for Geriatric surgery

- GeriatricsCareOnline.org

- HealthinAging.org

- Minnesota Elder Justice Center (elderjusticemn.org) provides support, information and resources to older and vulnerable adults and their loved ones around issues of abuse, neglect and financial exploitation.

-

Trellis | Optimizing well-being as you age (trellisconnects.org)

-

ISAR Screening Questions

No

Yes

- Before the illness or injury that brought you to the Emergency, did you need someone to help you on a regular basis?

0

1

- In the last 24 hours, have you needed more help than usual?

0

1

- Have you been hospitalized for one or more nights during the past six months?

0

1

- In general, do you have serious problems with your vision that cannot be corrected with glasses?

0

1

- In general, do you have serious problems with your memory?

0

1

- Do you take six or more different medications every day?

0

1

Total /6

Scoring: Score of ≥ 2 is a positive test

-

Click on Image to link to the Acute Frailty Network

-

Evidence-Based Senior Falls Prevention Programs

Program Name

Course Length

Session Duration

Participants

Target Population

Leaders

Key Features

Additional Considerations

Min

Max

Coordinated and licensed in Minnesota by Juniper. For information about training and the Juniper Network, contact Stacy Dunn sdunn@trellisconnects.org

7 weeks, plus 3-month booster

2 hours

8

14

Older adults (60+) able to walk indoors without assistance and who live independently and are cognitively intact

2 trained facilitators, or 1 facilitator and 1 peer leader

Focus on strength and balance, home safety, and guest experts to spark facilitated discussion

Guest speakers required. PT (3 sessions); medication, vision, and community safety experts (1 session each). Ankle weights must be available for participants. English only.

8 sessions,

4-8 weeks

2 hours

8

12

Older adults (60+) who are concerned about falling, live independently and are cognitively intact

2 trained leaders

Education on fall risk, physical activity, problem-solving

Can be either 1 or 2 sessions per week. Participants can do exercises while seated. Available in 8 languages

24 sessions, 8-12 weeks

1 hour

8

15

Older adults (60+) who live independently and are at risk of falling or have balance disorders or abnormal gait

1 trained leader

Mind-body exercise, improves balance, strength, and flexibility

Can be done seated or standing. Can become an ongoing class for participants after the initial sessions.

Other programs available in the public domain or through a licensing agency

20 sessions, over 10 weeks

45-60 min

8

20

Sedentary older adults at all ability levels, in a variety of settings, including certified nursing facilities, assisted living, independent living, and community senior centers.

1 trained leader per 20 participants

Health education questions and exercise are strategically inserted while playing bingo

Participants need resistance bands, stress ball, and curriculum reinforcements (prizes)

Ongoing, 2-3 times per week

1 hour

15

Community-dwelling older adults (65+) able to walk independently or with a cane.

1 trained leader per 15 participants

Strength, balance, and fitness program

Participants can do exercises while seated. Available in 4 languages.

Initial: 8 weeks 4 individual PT visits and exercise

Self-management: 4-10 sessions once per month

30 min

1

High-risk or frail older adults who do not have the endurance for other exercise classes

1 PT, OT, or PT assistant with support from other fitness/health workers

Pairs individual PT services with other group or individual settings

4 individual sessions with a PT along with individual or group exercise 3 times per week during initial phase. In self-management phase, participants meet individually or as a group once per month